- Home

- Michael P. Spradlin

The Enemy Above Page 8

The Enemy Above Read online

Page 8

He stood up and gauged the distance. He needed to get closer. Slowly, he moved toward the group until he was only thirty meters away. One of the soldiers—the sergeant, Anton thought—stood with his back to him. Taking careful aim, Anton chucked a rock with all his might. It flew through the air and struck the soldier between the shoulder blades, driving him to his knees.

“Was ist das?” the soldier shouted. The others raised their weapons and glanced about. But Anton was already on the move. As quietly as he could, he ran in an arc around the men, who were now yelling at one another in confusion. Taking careful aim, he hurled a second stone. This one struck one of the men in the thigh. He moved around the group again and threw a third. This time he missed. The stone skipped through the middle of the group.

The major ordered his men to shoot. Machine-gun fire spat in every direction. Anton dropped to the ground. The bullets whizzed over his head. When the firing stopped, he slowly stood and crept farther around the group. He chucked another rock. Ping! It hit one of the soldiers on the helmet, and the man staggered forward.

“Finden sie! Finden sie! Achtung!” the major shouted. Find them! The four soldiers took off running into the night while the major stayed behind to guard their prisoners.

Clutching the hatchet in his hand, Anton waited until the soldiers had disappeared. He circled slowly, quietly. When the major’s back was to him, Anton crept forward out of the darkness. The cruel man who’d taken his bubbe turned, and his eyes went wide with surprise just as Anton brought the blunt side of the hatchet down on his head.

“Too bad gestapo officers don’t wear helmets,” Anton whispered as the blow hammered the major to his knees. A hand raised the Luger, but Anton swung again. This swipe did the trick. The major slumped forward, landing face-first on the ground.

“Bubbe, Rina,” Anton said. “Come. We must hurry.”

When Von Duesen came to, one of his men stood over him, splashing his face with water from a canteen. Eberhardt shone a flashlight in his eyes. Von Duesen touched his fingers to the sore spot on his crown and they came away bloody. His head ached.

“Where are the prisoners?” he demanded.

“Gone, mein major,” Sergeant Eberhardt said.

“What? How could two women and a boy escape?” he said.

“We were attacked, mein major—”

Von Duesen pushed the canteen away and clambered to his feet. He felt woozy, but would not show weakness in front of his men. “We were not attacked, you fools!” He kicked a stone lying on the ground. “A boy threw rocks at us! They can’t have gone far! Find them!”

“But which way, mein major?” Eberhardt asked.

“I don’t care! It is an old woman, a mother, and a child!” He picked his Luger up off the ground. “Just find them!”

The four men split into teams of two and headed off into the black night, their flashlights working the ground as they searched the soil for any sign of tracks. They tried to cover as much ground as possible, but it was slow going. The potato fields were full of vines and made it difficult to find tracks.

“Beeilung! Ihr Idioten!” the major shouted. Hurry, you idiots. Von Duesen was despondent. How had everything gone so wrong? He could not return to headquarters empty-handed again.

He’d thought the partisan militia had attacked the half-track, but now he doubted that assumption. A militia patrol would consist of at least ten men. Wouldn’t they have gunned the gestapo down to rescue the prisoners? But instead they had thrown rocks. Militias were sometimes short on supplies, of course. Could they have run out of ammunition? That didn’t make sense. With ten men they would still have outnumbered his squad.

No, this was not a large group. And Von Duesen suspected it was personal. Someone could have followed them from the cave. If they were smart enough to tail the half-track, they might have been smart enough to sabotage it. And now they were attempting a rescue. He needed to find this mystery attacker.

If I return to headquarters with no prisoners, there will be consequences, Von Duesen thought. Karl knew he could be reassigned, demoted, or relieved of his command.

He could not allow that.

As the minutes passed, his men worked their way deeper and deeper into the fields. How could such feeble prisoners elude soldiers of the mighty gestapo? Von Duesen waited for an answer, his anger as complete as the silence of the night.

The quiet was shattered by the sound of machine-gun fire.

“Nein! Nein!” Von Duesen shouted as he ran toward his men. “Nicht schiessen! Nicht schiessen!” Don’t shoot. If the prisoners were killed they could not be questioned. They would not be able to help him make the area Judenfrei.

His boots trampled the earth. The men were more than a hundred meters away. When Von Duesen arrived at their location his heart sank. Smoke still curled from the barrels of their guns. A flashlight illuminated the scene.

On the ground lay the mother and her child. Their bodies were riddled with bullet holes and blood seeped through their clothing.

“Spread out!” Major Von Duesen ordered. “We will not leave this place until we find whoever has attacked us!” He cracked his knuckles. “But take them alive. Do you hear me? Do not shoot them!”

Now more than ever he needed answers to his questions.

Anton did not know what to say. He and Bubbe watched the soldiers across the field arguing over the bodies of Rina and David.

Why had the gestapo fired their weapons? Surely, to interrogate their prisoners and find out where their friends and neighbors were hiding. He felt responsible. An enormous wave of guilt washed over him. He should have insisted Rina come with them. But she hadn’t wanted to find the Priest’s Grotto. She’d said she and David would be safer on their own. And now they were dead.

“Oh, Bubbe,” Anton moaned. “What have I done? What have I done?”

Bubbe took his hand and squeezed it hard. “Anton, you did nothing wrong. Those men over there are pure evil. You have never seen it before. They have no conscience, no feeling, no remorse. You gave Rina and her son a chance. You did all you could do. Now you must pull yourself together. We will grieve for Rina and David later.”

Anton knew she was right. But still, he felt a sadness he had never known before. It weighed on him as heavy as the boulders that had trapped him only days earlier. The only way he could wash away his grief was to focus on getting Bubbe to safety. But even then, he struggled to keep the guilt he felt at bay.

“I am sorry, Bubbe,” Anton said.

“No, Anton, my child. It was God’s will.” Again, Bubbe spoke of God. Anton wondered how she could maintain her faith in such circumstances.

They walked on in silence. Each potato field they crossed looked the same to Anton. Time seemed to slow, the only marker the growling rumble of his belly. When they stopped to rest, Anton dropped to his knees and pulled a vine from the soil. Raw potatoes were chalky, but they were the only food around. He picked a dozen more and secreted them in his blanket. He and Bubbe would not go hungry. But they would need to find water soon.

“Bubbe?” he asked.

“Yes?”

“What do we do now? How do we find the Priest’s Grotto?”

“We head north. Dmitri says the area is full of partisans. There are people there who have no love for the gestapo. If we can find them, they will help us find the caves where Dmitri and the others are headed.”

“How far is it?”

“I do not know, Anton. I’m not even sure where we are now. Soon, daylight will come. Perhaps then we can determine where we are. But first we must find a place to hide.”

Anton had no idea where that might be. In the starlight, all he could see were potato plants. Bubbe could not move quickly and it would be dawn soon. Already the eastern sky was growing lighter. If the major had indeed called reinforcements, soon the entire area would be crawling with gestapo.

Yet they had no choice but to keep walking. So they did, step after step in the soggy soil. Ev

ery bird that fluttered into the sky at their approach caused Anton’s heart to thunder in his chest. He tried to will his grandmother to move faster, but he knew she was going as quickly as she could. Anton kept count, and every ten steps he looked behind him, studying the horizon and making sure that no one followed them.

After another hour, Anton spotted a copse of trees. Even better, there was a farmhouse, barn, and several small outbuildings on the other side of them.

“Bubbe, wait,” Anton whispered. He gestured toward the farmhouse. It appeared deserted. With dawn approaching, someone should have been stirring inside. On a working farm, a lamp would be lit or a fire started before sunup. But the windows remained dark.

Even so, he tried to remain optimistic. “Perhaps the farmer can help us,” he said.

Bubbe shook her head. “No, Anton. You must never approach someone you do not know. We are Jews. Many of our neighbors are not. They will turn us in to save themselves from the gestapo. We should keep going.”

“Bubbe, please listen. I am tired. You are tired. We need to rest. If we cannot knock on the door of the house, perhaps we can sneak into the barn. There must be a hayloft. No one will know if we sleep there for an hour or two. Then when the sun comes up we can figure out where we must go next to find Uncle Dmitri. We can find places around the farm to hide until nightfall.”

“I don’t know, Anton,” she said as she studied the house. Her shoulders slumped and she leaned heavily on her walking stick. He knew she was in pain, though she would die before she admitted it.

“Bubbe, we cannot continue after the sun comes up. These fields are too open. We need to hide. Besides, they have water,” he said, pointing to a hand pump a few meters from the barn.

She studied her grandson. “When did you grow up, Anton?” she asked. “It was only yesterday you were toddling along behind your father, trying to do everything he did. Now you are almost a man.”

Looking up at the barn, she smiled. “All right, we will do as you say. We will hide in the barn. Wait until darkness comes again. Then we will find your Uncle Dmitri.”

Anton felt a tremendous sense of relief. Still, he was cautious. As they approached the barn, he kept the trees between them and the house. His instincts told him the house was deserted. Whoever lived there had packed up and left. But he wasn’t sure enough to take a foolhardy risk. Anton kept his eyes on the house, with its neglected flower trellises and worn front steps, as they crept past it and headed for the barn.

Bubbe started for the door, but he gently took her elbow to stop her. He pointed to the pump. “Water first, Bubbe,” he said. The pump held a tin cup on a hook. It was made of rusted iron, but looked to be in working order. The trouble was, a pump like this needed water poured down the shaft to prime it. And there was no water available to use.

Anton glanced around. If only there were a puddle or a rain barrel nearby. But he saw nothing. Then he spied a watering trough on the side of the barn. He removed the cup and headed around the corner to investigate. A centimeter of tepid water was a most welcome discovery! It would be enough. He scraped the cup along the bottom of the trough. Returning to the pump, he poured some of the water down the shaft and grasped the pump handle. He knew from experience the metal parts of the pump would squeak and groan when he lifted the handle. But if they wanted a drink, he had no other choice.

He pulled the handle upward and was rewarded with a loud shriek. To Anton it sounded as loud as a cannon shot. He poured more water down the pump shaft and the sound softened, but the pesky squeak would not go away. If there was anyone in the house it would surely alert them. Up and down he worked the handle, slowly priming the pump with the remaining water from the cup.

At first he thought the well might be dry, but then he heard a gurgling sound as water worked its way up the pipe and finally spilled out of the spigot. He pumped harder—he knew the water would be dirty and undrinkable at first. When it cleared, he rinsed out the cup, filled it to the brim, and handed it to Bubbe. She drank it dry in about three gulps. He filled it again and again she drank. Only when she was done did Anton take a turn. The water tasted earthy, but he didn’t care. It was like heaven on his tongue. He had not realized how thirsty he was. He and Bubbe each drank another cup. All the time, he kept his eye on the house. Though he suspected it was empty, he couldn’t help expecting the door to open or the windows to illuminate at any moment. But the house remained still.

When he and Bubbe finally entered the barn, he flipped on his flashlight. The room looked forgotten. An old tractor sat in front of a double door, but its tires had long gone flat. A hoe, a shovel, and a sickle hung on the wall. Very little else was left behind.

There were empty stalls where animals had once been kept. Now all that remained was a large pile of hay. The farmers had either turned their livestock loose or hitched them to a cart when they were leaving. Anton took the hoe from the wall and worked it through the hay, making sure it was free of rats and mice. Nothing scurried away.

“We can sleep here, Bubbe,” he said. “If you are hungry, I have a few potatoes.”

“No, Anton. I am too tired to eat, and right now that pile of hay looks like a wonderful, comfortable bed.” She lay down on the hay, groaning in pain. She pulled her shawl around her shoulders and closed her eyes. A few moments later, she was softly snoring.

Anton went to the barn window and stared outside for a long time. If the Germans came, they’d never be able to run—not with Bubbe moving as slowly as she did. So he would have to be prepared. The door to the barn opened inward, but latched shut on the outside. He propped the hoe and shovel against it. If anyone pushed the door open, the clattering noise of the falling tools would wake him. Then he removed the sickle from the wall and checked the edge with his thumb. The blade was pocked with rust spots, but the edge was still sharp.

This will make a much better weapon than my little hatchet, he thought to himself as he lay down next to Bubbe.

Anton’s eyelids felt heavy. Seconds later, he was asleep with the sickle’s handle clutched tightly in his hand.

Major Von Duesen was livid. The sun had risen an hour ago, and he had been ordered to wait by the bodies of the dead woman and her child until General Steuben arrived. He understood that he had failed miserably. But the longer he waited, the farther away the old woman—and whoever had freed her—were getting, making them that much harder to catch.

He had been furious with his two privates for shooting down the Juden. They knew he wanted the fugitives captured alive. If General Steuben did not relieve him of his command for this debacle, Karl would make sure those two simpletons were reassigned. He would have them sent to the Russian front. But Karl had to admit that the world would not mourn the loss of two more Jews. If the woman was still alive, she and her child would have been sent away after her interrogation. They probably would have died anyway. Perhaps they had been spared future suffering. But really, that did not matter in the least. Their deaths were meaningless.

Headlights cut through the morning mist as three half-tracks and a truck carrying a platoon of soldiers turned off the road and rolled to a stop. The column was led by a staff car, decorated with a Nazi flag on either side of the hood flapping in the morning breeze. The sight of the car filled him with dread.

General Steuben did not wait for his driver to open his door for him, emerging from the Mercedes with grim purpose. If there was one thing Karl admired about his commanding officer, it was that General Steuben did not stand on ceremony or let the trappings of his rank get in the way of duty. He was a no-nonsense soldier who always got right down to business. And this morning, the business at hand meant explaining the absence of prisoners. Von Duesen suddenly wished he were anywhere but here.

The general’s uniform was immaculate, his boots polished and gleaming. But he did not hesitate to walk into the muddy field where Von Duesen and his men stood near the bodies. Von Duesen and his men came to attention.

“Heil Hitler, mein gen

eral,” he said.

The general repeated the salute. “Heil Hitler, Major.” He did not look at Von Duesen. Instead, he studied the bodies lying in the field.

“Report,” he ordered.

Von Duesen recounted the events of the previous evening. He told the general about tracking the two Jewish men to the cave, and the ambush that they’d executed. And how he had not yet been able to make radio contact with the lieutenant he had left in charge of rounding up the rest of the Jews who had been hiding in the cave’s many tunnels. The older man’s expression never changed.

“So you discovered a hiding place with many Juden. You left with three prisoners. Why did you not stay until the cave had been searched?” he demanded.

“The old woman, mein general,” Von Duesen said. “She was obviously an important elder. A symbol and leader of the Juden in the cave. In truth, I thought of shooting her there. To break their spirit. But then I thought it wiser to remove her for interrogation. I believe she is giving the others instructions. A coded message of some kind. It seemed a better idea to remove her.”

“I see,” the general said. “And how did she escape?”

“We were attacked,” he said.

The general’s eyes narrowed. “Attacked? By who?”

“I do not know,” Von Duesen replied. “At first I thought a partisan militia, but now I do not think so. They had no weapons and—”

“No weapons? Then how were you ‘attacked’?”

Major Von Duesen looked down. He found himself momentarily unable to speak.

Sergeant Eberhardt, perhaps hoping to save himself from a demotion, spoke up. “We were surrounded, Herr General,” he responded with conviction. “And we were outnumbered. In the confusion, the prisoners escaped.”

“I do not understand,” Steuben huffed. “If partisans attacked you, why are you not dead? Why did they not gun you down and take your prisoners? Someone please explain this to me.”

General Steuben’s piercing blue eyes bored into Eberhardt. Karl had no great love for his sergeant. The man tried too hard to please. He didn’t think. And he was no match for Steuben’s pointed questioning. “We do not believe they were armed, Herr General,” Von Duesen interjected.

Trail of Fate

Trail of Fate Alcatraz

Alcatraz Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime

Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime Keeper of the Grail tyt-1

Keeper of the Grail tyt-1 To Hawaii, with Love

To Hawaii, with Love Out for Blood

Out for Blood The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

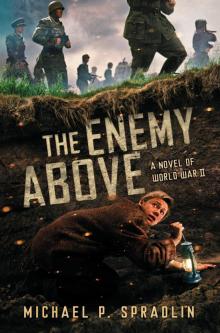

The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me The Enemy Above

The Enemy Above Menace From the Deep

Menace From the Deep It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies

It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies Feeding Frenzy

Feeding Frenzy 3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me Keeper of the Grail

Keeper of the Grail Prisoner of War

Prisoner of War Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill

Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill Live and Let Shop

Live and Let Shop Blood Riders

Blood Riders Ultimate Attack

Ultimate Attack