- Home

- Michael P. Spradlin

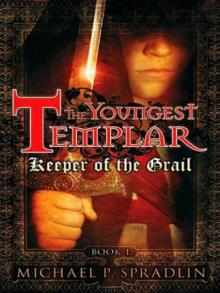

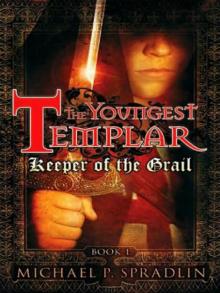

Keeper of the Grail tyt-1

Keeper of the Grail tyt-1 Read online

Keeper of the Grail

( The Ypungest Templar - 1 )

Michael P. Spradlin

Michael P. Spradlin

Keeper of the Grail

PROLOGUE

This time in which we live will one day be called the Dark Ages. What a fitting name. I have done all I can to stand against the darkness, though I still feel it pressing in around me. I had hoped I would find safety here, but that has turned out to be a foolish dream. I have come so far. Not much farther now. Can I bring an end to this?

I am alone now. Sir Thomas sent me from Acre with a few coins, and I’ve kept his sword and ring. I have enough, if I am careful, to see me through this duty, but there may come a day when I must sell the sword and ring.

I miss Sir Thomas. He was kind, and there was always food. The work was hard and full of danger, for what is a Crusade but another word for war? He trained me well and was not overly pious like so many of his fellows.

Now I must decide what path to take. I have traveled far and endured much to fulfill a promise to a doomed knight. Should I continue on to face those who would see me dead for what I possess? In the last few months I have learned much about fate. For Sir Thomas was no ordinary knight. My master and liege, Sir Thomas Leux, served his God as a member of the Knights Templar. And in the simple leather satchel that never leaves my shoulder, I, a mere orphan, an unworthy soul, am now the protector of the Holy Grail, the most sacred relic in all of Christendom.

For centuries legend has said that this simple bowl-shaped chalice caught the blood of Christ as he died upon the cross. And because it once held the blood of the Savior, some believe it to have magical properties. To find it has been the life’s goal of countless men.

I heard some of the Templars say that whoever possesses the Grail will be invincible; their armies cannot be defeated in battle. This is why the knights were so fanatical about keeping it hidden, lest it fall into the hands of the Saladin. Truth be known, I do not think much of these stories. If the Grail really makes one’s army invincible, then why didn’t the Templars carry it into battle and drive the Saladin and his warriors from the field? Perhaps the Saracens have their own sacred relic that cancels out the power of the Grail?

Whatever its legend, even the idea of the Grail is a powerful thing. Though it may or may not be the true cup of Christ, it is a symbol. And in my short life, if I have learned anything, I have learned the power of symbols, from the bright red crosses on the Templars’ tunics, to the crucifix that hangs in the chapel of the abbey. Symbols can make human beings behave in less than honorable ways.

No matter the cost, I must now carry this valuable thing to safety. Sir Thomas considered it my duty.

I consider it my curse.

ST. ALBAN’S ABBEY, ENGLAND MARCH 1191

1

Though I am called Tristan, I have no true name of my own. It was Brother Tuck who found me on St. Tristan’s Day, nearly fifteen years ago. He is a kind and gentle man, but a deaf-mute, and unable to even write down for me how I came to be here. The abbot, a much sterner sort, tells me that I was found that August night on the steps of the abbey. A few days old at best, hungry and crying, wrapped in a soiled woolen blanket.

I’m told the sound of horses could be heard riding away through the night, but since Brother Tuck was the first to find me, we know not if he saw or even glimpsed the riders. The abbot said that two of the brothers followed the tracks into the woods but soon lost the trail.

He also thinks I must be of noble blood. No peasant could afford to own such horses, and it is unlikely a poor farmer would abandon an infant that might one day grow strong enough to help him work the farm. Nor would any illiterate peasant likely be able to write the note that was neatly tucked into the folds of my blanket. On a simple scrap of rolled parchment, wrapped with red ribbon, it read, “Brothers: We bestow onto you this innocent child. His life threatens many. Remind him that he was loved, but safer away from those who would wish him harm. We will be watching over him until it is time.”

So whoever left the note must consider me safe now that I am nearly fifteen. For as near as anyone at the abbey can tell, no one has ever come here and asked about or “watched over” me in any way. Perhaps my parents, whoever they are, were unable to fulfill that promise.

The monks were always kind to me, but they were Cistercians and believed that one was never too young to work. I earned my keep there. However, I bore them no ill will, for the monks worked just as hard as I did. I lived at St. Alban’s for all of my life, and my earliest memories were not of the names and faces of the monks, but of chores. We were a poor abbey but grew enough crops and raised enough sheep and goats to get by. Our needs were few. There was wood in the surrounding forest to see us through each winter. The gardens provided us with plentiful vegetables, and the fields gave us wheat, which we turned into bread. If there was ever anything else we needed, the brothers traded for it in Dover or one of the nearby villages.

It was a quiet and calm existence, but the work was endless. The garden was my main contribution to the abbey. Brother Tuck and I tended it from planting in the spring to harvest in the fall. Working the hoe through the soil was quiet work, and gave me much time to think. The garden sat in a sunny spot behind the abbey, and once the rainy spring was over, the weather was usually fine and fair.

Our abbey was on the travelers’ road a day’s ride northwest of Dover. There were thirty monks in service there. Built many years ago it rose up out of the surrounding forest like a small wooden castle. It was simple in its design, because Cistercians are not frivolous, believing man is here to serve God, not adorn his buildings in finery.

Still, it was a comfortable place, inviting and welcoming to the few travelers who passed our way. The main hall where the brothers gathered to dine and pray was well lighted by the windows that rose high in the peaks. The surrounding grounds were neat and well tended, for the brothers believed that keeping things orderly kept one’s mind free to focus on God.

Except for the forest around the abbey grounds, and a trip to Dover three years before, I had seen no more of the world-though that was not all I knew of it. The monks offered shelter to travelers along the road to Dover, and from them I heard things. Exciting things happening in far-off places that made me wish for a chance to leave and see them for myself. Some told tales of wonder and adventure, of magnificent battles and exotic places. Recently, most all of the talk was of the Crusade. King Richard, who some called the Lionheart, carried out his war in the Holy Land, and it wasn’t going well. King Richard had been on the throne for almost two years, and had spent most of his time away from England fighting in the Crusades. He was called the Lionheart because he was said to be a ferocious warrior, brave and gallant, and determined to drive the Saladin and his Saracens from the Holy Land.

The Saladin was the leader of the Muslim forces opposing King Richard. He was said to be as courageous and fierce a warrior as the Lionheart, consumed with ridding the Holy Land of Christians. Even those who said that God was on our side conceded that defeating the Saladin would not be easy.

For the monks, the news from the east was of particular interest. To them, the rise of the Saladin was a signal that the end of days was near. Perhaps the Savior would soon come again.

These were my thoughts, on a clear and sunny day, as I worked beside Brother Tuck in the garden. Brother Tuck was a large man, strong and sturdy, with a generous heart. Though he couldn’t speak, he made a soft humming noise while pushing his hoe through the soil, moving to some rhythm only he felt. He could not hear the riders approach, or the sound of horses’ hooves pounding across the hard ground, or the clang of chain mail and sword as the knights reined up a

t the abbey gate.

Knights wearing the brilliant white tunics with red crosses emblazoned across their chests. The Warrior Monks. The famous Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon. Known to all as the Knights Templar.

2

The knights rode through the abbey gate into the shade of the tall trees lining the courtyard. I counted twenty in the group, well mounted, their chain mail gleaming in the morning sunlight. The abbot walked down the front steps to greet the travelers.

“Welcome, soldiers of God,” he said.

I stopped working, leaning on my hoe to watch from the garden. I tapped Brother Tuck on the shoulder and pointed to the Templars astride their horses in the courtyard.

A tall, thin knight wearing a gilded cowl dismounted, removing his helmet, and greeted the abbot.

“Thank you, Father,” he said. His voice was high pitched and seemed out of character for a warrior. Templars were forbidden to shave their beards, but this one’s was sparse, as if he could not grow a full one. His face was pinched as though his helmet were too tight and had forced his features into a permanent scowl. He wore a Marshal of the Order emblem on his tunic, which meant he was in command.

“My name is Sir Hugh Monfort; we are bound for Dover and the Holy Land.” He pointed to another knight, who dismounted and stood holding the reins of his horse. “This is Sir Thomas Leux, my second in command. We have ridden far this day and wish to rest here this evening,” he said.

“You are welcome to all that we have, sire,” said the abbot. “We are a poor abbey but rich in spirit. I shall have some of the brothers assist you with your horses and you shall dine with us this evening.”

Sir Hugh gave the order to his men to stand down. The knights dismounted. Some of them began to stretch, shaking their legs and arms, tired as they were from their journey.

“Tristan!” I heard the abbot call my name.

“Yes, Father?” I asked as I ran over from the garden.

“Make room for our visitors’ mounts in the stable, then return with some rope to help them hobble the rest here in the courtyard. They are welcome to our feed and hay,” he said.

“Yes, Father,” I said.

Sir Thomas, who had overheard our conversation, stepped forward, removing his helmet and holding the reins of his horse in his hand. He was a head taller than I, and a large battle sword hung at his belt. Though his face was covered in dust, I could see a long scar on his cheek that traveled from his right eye down his face until it disappeared in the tangle of his beard. His hair was a reddish-brown color, and an easy smile came to his face.

“After you, lad,” he said.

I led him across the courtyard while Sir Hugh remained behind talking with the abbot. The other knights mingled with some of the brothers, waiting for me to return with rope. Our path led around behind the main building to the back where our outbuildings lay. We kept a small stable there, with a brace of draft horses, two milk cows and some goats. In addition to my garden duties I cared for most of the animals at the abbey.

As we walked toward the stables, the knight introduced himself.

“My name is Sir Thomas Leux,” he said.

I stopped and turned to bow, but he waved me off. A knight was nobility, and it was my obligation to bow to him.

“Ah, no need to bow. We don’t stand on such formalities in times such as these,” he said. “Tristan, is it?”

“Yes, my lord,” I said, still partly bowing out of habit.

I noticed that Sir Thomas’ tunic was frayed and that his boots were caked with dust and mud. His mail was tarnished, the rust showing through in several places. The shining hilt of the sword that hung at his belt, however, gleamed in the sunlight.

“I beg your pardon, but you seem a bit young to be a brother,” he said.

“I have not taken vows, sire,” I said. “I am an orphan. The monks have raised me from a babe.”

“Ah. Well, you grow strong and straight. It would seem they do right by you,” he said.

As we reached the stable, I pulled open the door, taking the reins of his horse and leading him to one of the empty stalls.

“Is the stable your duty?” Sir Thomas asked.

“Yes. Among other things,” I answered. “I also work in the garden, I assist the cook in the kitchen with the morning and evening meals and each week I’m required to gather one cord of firewood from the forest so that we have enough for cooking and for the fireplaces in the winter. I also help with the harvest. Then if anything else requires doing, it generally falls to me.”

“An impressive list of chores. Are you sure you didn’t leave anything out?” asked Sir Thomas, with one eyebrow raised.

“No, sire, I’m fairly certain that covers it,” I said, embarrassed that I had shared far too much information with a knight who probably had no interest in my day-to-day affairs.

“Well, as for the stable,” he said, looking about, “it would seem the brothers have chosen wisely. This may be the neatest, cleanest stable I’ve ever seen,” he added, laughing, as I lifted the saddle from his horse and laid it on the rail of the stall. Removing the saddle blanket, I rubbed the horse gently on its hindquarters. Then I filled the manger with hay and emptied a water bucket into the trough for the horse to drink.

“I’ll need to help the others with their mounts,” I said, “but when I’m finished with them, I’d be happy to groom the horse for you.”

A look of weariness mixed with gratitude came over Sir Thomas’ face.

“Don’t trouble yourself, lad,” he said.

“It’s no trouble. I see you ride without squires or sergeantos so you can probably use the help. Besides, the abbot says we have a duty to assist the Crusaders all we can.”

“Does he now?” Sir Thomas asked. “Very well then, I accept your kind offer.”

“I can show you where the guests sleep in the abbey if you’d like to follow me, sire,” I said.

Leaving the stall, I grabbed a coil of rope from a hook on the wall, looping it over my shoulder. The door to the stables had swung shut in the breeze, and as I pushed it open, it caught a gust of wind, slamming backward on its hinges with a bang.

Just outside the door, I watched in horror as Sir Hugh’s mount reared up in alarm, whinnying loudly, spooked by the loud sound.

“Haw, haw!” he yelled, taking a length of the reins and striking at the horse as it bucked and tossed near him. This only made the stallion rear again and then jump sideways. When it landed, Sir Hugh lost his grip on the reins and tumbled to the ground. The stallion reared again, landed on four legs and stumbled, crashing into the fence. Its foreleg struck one of the timbers and began bleeding from a small cut.

Sir Hugh lay in a heap on the ground, and while the stallion’s head was down, I leapt forward, hugging it hard around the neck with my arms before it could rear again. I calmly whispered to the horse, holding it fast as it tried to jerk away from me. In seconds the horse stopped its rant and stilled, standing with its foreleg gingerly touching the ground. It nickered and whinnied, but had finally calmed.

I let go of the horse’s neck and took hold of the reins. Sir Thomas stood in the doorway of the stable with a smile on his face. “Well done, lad,” he said.

“Well done? Well done?” shouted Sir Hugh as he scrambled to his feet. “This idiot boy’s carelessness lames my horse and nearly kills me-and you tell him well done?”

I winced at his words. Sir Thomas glared at Sir Hugh but said nothing for the moment.

“You stupid boy!” Sir Hugh strode to where I stood. “You imbecile! This stallion cost the Order thirty pieces of gold. Thirty! And his leg is ruined.” Sir Hugh puffed out his cheeks, his face a mask of consternation.

“It is only a small cut, sire,” I said. “I doubt the horse is lame. Brother Tuck has many-”

Sir Hugh stood there and with exaggerated motion, began putting on his chain-mail gloves.

“How dare you?” he hissed, stepping toward me. I drew

back as he grasped the front of my shirt with one hand. I tried to twist away, but didn’t dare let go of the stallion’s halter, afraid that it might rear again. His chain-mailed fist drew back to strike me and I tried my best to duck, keenly aware that this was going to hurt.

3

Except it didn’t. The blow never came.

“Hold!” a voice said. I straightened up to see Sir Thomas grasping Sir Hugh’s arm from behind with one hand. Sir Hugh struggled vainly to free his arm, but could not shake the grip of the stronger knight.

“Release me!” Sir Hugh spat. “I demand that you unhand me this moment! How dare you assault the Marshal of the Regimento?”

“Being Marshal does not give you leave to thrash an innocent boy,” Sir Thomas replied calmly.

“That boy has ruined my prized stallion.”

Sir Thomas released his hold on Sir Hugh but moved around him to a place between us. I did not know what to do. It had all happened so fast. Now I was at the center of a conflict that I suddenly felt had little to do with me.

“I’ll be happy to tend to the horse myself, Sir Hugh…,” I started to say, but Sir Thomas turned to me with a raised eyebrow. Immediately I wished I’d kept my mouth shut. He turned back to face Sir Hugh.

“I demand that you step aside or I will bring you up on charges!” Sir Hugh was in a rage as spittle flew from his mouth. It looked at any moment like he might draw his sword and strike down Sir Thomas.

“Do so, and I will bring you up on countercharges of conduct detrimental to the Order. Had the stallion reared again you may have been killed or gravely injured. The boy likely saved your life. The horse doesn’t appear to be seriously hurt. I’m sure the monks can apply a salve and bandage to the cut. Now you need to control yourself and take leave.” Sir Thomas, I noticed, spoke very calmly. His voice was steady and his tone even.

Trail of Fate

Trail of Fate Alcatraz

Alcatraz Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime

Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime Keeper of the Grail tyt-1

Keeper of the Grail tyt-1 To Hawaii, with Love

To Hawaii, with Love Out for Blood

Out for Blood The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me The Enemy Above

The Enemy Above Menace From the Deep

Menace From the Deep It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies

It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies Feeding Frenzy

Feeding Frenzy 3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me Keeper of the Grail

Keeper of the Grail Prisoner of War

Prisoner of War Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill

Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill Live and Let Shop

Live and Let Shop Blood Riders

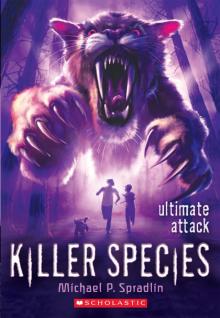

Blood Riders Ultimate Attack

Ultimate Attack