- Home

- Michael P. Spradlin

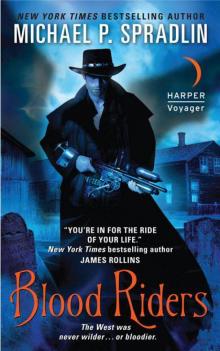

Blood Riders Page 13

Blood Riders Read online

Page 13

“Enormously entertaining,” Hollister said. “Are you always going to be sitting there?”

“Sitting where?” Pinkerton asked, not looking up from his paperwork.

“At the desk, on this train? I just wondered if every time we came back here, we’d find you, is all. Maybe one of Dr. Van Helsing’s traps around the windows and doors is holding you here?” Hollister asked.

Pinkerton looked up, studying Hollister to see if he was serious. He couldn’t tell.

“What did the senator have to say?” he asked, changing the subject.

“Not much. His son is apparently a weakling, the camp was attacked by Utes, not vampires, and he doesn’t like jokesters or people who aren’t ‘punctual,’ ” Hollister said. “I’m pretty sure he gave his man Slater the order to have me killed after I left.”

“Why would he do that?” Pinkerton asked.

“It’s what I would do,” Hollister said.

Pinkerton stared off into space a minute, as if considering all the facts.

“I’ll have a couple of my operatives dig into this Slater fellow, see what they can turn up. Does the senator believe in what it is we’re dealing with here?” he asked.

“I’m not sure,” Hollister said. “What do you think, Sergeant?”

Chee hesitated. He was not used to contributing to conversations like this, or being asked for his opinion. Most of his time in the army—his life, actually—he had been overlooked and ignored. He could deal with rowdies like Slater. He was comfortable in that world. But Hollister and Mr. Pinkerton and Dr. Van Helsing and all their educated talk were new territory. Monkey Pete he liked a lot. So far.

“I think at first . . . no . . . he didn’t believe it. Assumed it was Indians, like the major says. But he probably sent his man Slater to the camp and Slater knows it wasn’t Indians. And now the senator has come to realize he’s dealing with something he doesn’t know anything about. He’s worried of what it might cost him,” Chee said.

Pinkerton nodded. “And rest assured, the senator will try to glean any information he can from you. It is incumbent upon you both that it stays with us.”

“Going to be hard to keep it under wraps for long if we go traipsing about in this fancy train. It won’t be long till somebody from a newspaper knocks on our door to see what we’re up to. And if we use any of our fancy gear in public . . .” Hollister let the words hang there.

“Be that as it may, people may wonder about the train, your weapons, all they wish. But any word leaking out about these creatures can only cause needless panic,” he said. Pinkerton reached in his briefcase and pulled out two badges, handing one to Hollister and one to Chee. “I asked the president for one more thing that might help both of you . . . adjudicate this matter. He had the attorney general sign the commissions this morning. Congratulations. You’re both U.S. Marshals.”

Hollister and Chee looked at the badges in their hands and then at each other.

“You have the authority to make arrests, cross state lines in pursuit of criminals, and pretty much anything you might need in the way of legal recourse. You can even go back and arrest the senator as a material witness if you want,” Pinkerton said.

“I can?” Hollister asked.

“Don’t,” Pinkerton said. “I’d keep those in your back pockets, and only use them if necessary.” He stood up, gathering his papers. “I’m leaving for Washington within the hour. . . .”

“You aren’t taking our train, are you?” Hollister interrupted.

Pinkerton stared at him with knitted brows.

“It’s just . . . I’ve . . . well, I’m very attached to the train,” Hollister said.

“Really. After just a few nights?” Pinkerton asked, finally getting the joke.

“I fall easily,” Hollister said.

“So it appears. No, Major. As I promised you in Leavenworth, the train is at your disposal. I’ll be taking other transportation back to Washington. I will expect to be updated regularly. Wires sent by the onboard telegraph will get to me. Monkey Pete is also an accomplished telegrapher.”

“Is there anything Monkey Pete can’t do?” Hollister asked.

“No,” Pinkerton said, snapping his briefcase shut. He shook hands with Hollister and Chee.

“Be careful, gentlemen,” Pinkerton said before departing the car. “I’ll be back from Washington in a few weeks. Hopefully, you’ll have this wrapped up long before then. Try to do it quickly; more people getting killed is not going to be helpful in the long run.”

“And don’t worry, Mr. Pinkerton, we’ll be careful too. Your concern is appreciated,” Hollister said.

Pinkerton was again caught off guard by Hollister’s specious manner. He made a little growling sound in his throat and left.

“You didn’t tell him about whoever was following us,” Chee said to Hollister after Pinkerton was gone.

“Knew I was forgetting something,” Hollister said. “I had a feeling he might be leaving soon. I wanted to make sure he’s gone so we can start on the real work.”

“The real work, sir?”

“Yes. We wouldn’t be here without Pinkerton, and he’s in charge. But I told him in Leavenworth I make the decisions on how we hunt these things. Now that he’s out of here we can get started.”

“Get started where, sir?”

“James Declan, Junior,” Hollister said.

Chapter Twenty-one

Senator Declan’s mansion sat on a rise overlooking the city. It was an impressive structure, four stories high, and having just met the man, Hollister had no doubt it was the finest in Denver. The senator did not appear to be the kind of man who would live in the second-best house.

“We should be on horseback,” Hollister said.

“Sir?” Chee answered.

“Walking up like this, it’s a little . . . diminishing. We should ride up on horses. Big horses. After all we’re U.S. Marshals now,” Hollister said, fingering the badge in his back pocket.

“Yes, sir,” Chee said.

“Chee, we’re on a mission here. We aren’t in uniform. You’re going to have to stop calling me ‘sir.’ You can call me Jonas. You can call me Hollister. I’ll even let you make up a good nickname if you’ve a mind to. But I think if you keep calling me ‘Major’ or ‘sir,’ it’s going to be a problem at some point.”

“Yes, sir, I understand, sir,” Chee said.

“Chee. You just did it again.”

“Yes, sir.”

“I give up. ‘Sir’ away, Sergeant.”

They had reached the tall wrought-iron gate in front of the mansion. Terraced steps led up in flights of four to a good-sized veranda. The lawn was meticulous, the brick stairs perfectly aligned. The columns were painted bright white and the door, perhaps the largest Hollister had ever seen, was polished oak. Standing in front of it, he rapped the brilliantly polished brass knocker several times. They waited what felt like several minutes, the heat of the day slowly rising, and Hollister was about to knock again when the door creaked open.

An elderly black man answered. He was slightly stooped and his hair was peppered with gray, but his eyes were bright and wide-set in his face. He wore a white waistcoat with trim black trousers and white gloves.

“You must be Silas,” Hollister said.

“Yes suh, can I help you?” There was just the slightest hint of a Southern accent in his voice. Hollister knew it well from his time at the Point. His first year, there had still been a few classmates and instructors from the Southern states. But when the war broke out, they all left to fight for the Confederacy.

Hollister handed Silas the senator’s card.

“We’re here to see young Mr. Declan,” he said.

“Yes, suh. I was told to expect you,” Silas said. “Please follow me.”

They entered the house into a foyer bigger than most counties. It was as if the house grew in size once you were inside. The ceilings had to be at least thirty feet high.

There was a g

rand staircase on the right, and on the left was a parlor full of fine furnishings, with large couches and upholstered chairs, which Hollister thought looked incredibly uncomfortable. Silas was nearly halfway up the stairs by the time he’d taken it all in.

The stairs were carpeted and led to another high-ceilinged long hallway with a large stained-glass window at the end that gave some light. Silas walked slowly and finally reached the last room on the right. Hollister and Chee stopped gawking and hustled to catch up with the butler, who had already entered.

They found a large, gloomy room that smelled of stale air and unwashed things. Against the far wall was a large four-poster bed, draped in a flimsy canopy. There was a small lump of twisted bedclothes in the middle of it and Hollister thought the pile of sheets and blankets might include a man but he couldn’t be sure. A tray of uneaten eggs and coffee sat on a small table nearby.

“Master Declan, suh. I’m very sorry to disturb you, but you have visitors,” Silas said.

There was no movement. Hollister glanced at Chee, who stood with his feet spread, his thumbs hooked over his gun belt. He looked uncomfortable and Hollister wanted to ask him why.

“Young James . . . come on now . . . you need to get up and speak to these gentlemen,” Silas prodded.

A low murmur came from beneath the bedclothes but Hollister could not make it out.

Silas bent over next to the head of the bed and whispered to the pillows. Finally, a head emerged, covered in shoulder-length black hair that had not been washed in some time. A bearded face turned and one eye opened, squinting to focus on the two men. The familiar fetid aroma of drunken sweat reached Hollister. Declan was trying to deal with what he had seen by living inside a bottle.

“You must be James Junior,” Hollister said.

“Don’t call me that,” the young man groused. “Silas, what are they doing here?” Declan asked with an aching groan in his voice.

Silas had moved to a spot at the foot of the bed, his white-gloved hands crossed in front of him. His stance said he was not listening to the details, but stood ready to intercede on young Declan’s behalf, if need be. Hollister thought back to his meeting with the senator and wondered what such a man could have done to inspire this kind of loyalty. But then he had known officers like Custer, who did not deserve the dignity or the honor of the men who served them.

“Master Declan, your father sent them. They just want to talk is all, suh,” he said quietly.

“No,” James said, burrowing back under the covers.

“I saw them too,” Hollister said.

Declan’s head reappeared.

“What you saw in the mining camp . . . I saw them before . . . they were in Wyoming then. But I saw them. They killed my men,” Hollister said quietly.

Declan stared at Hollister a long time, his eyes wild. Finally, he twisted his way out of the sheets and sat on the side of the bed. He was dressed only in long johns. He was skinny and looked like he hadn’t eaten in months, and his chest and arms were streaked with sweat and grime.

“They were fast and strong,” Hollister said. “One of them was big, with long white hair . . . he . . .”

“Blood devils!” Declan shrieked, interrupting Hollister.

Hollister flinched. He remembered the young girl, starving and nearly dead from thirst, and how she had cried over and over, mumbling “blood devils . . . blood devils . . .”

“Yes, the blood devils,” Hollister said. “I saw them too.”

“They killed . . . everyone. Chauncey. Faulkner. Reynolds. Marin. Ole Mack. Red eye. Doyle. Nickerson. Frederick. D’Agostino. Miller. Spencer. Quarles.”

Hollister was confused for a moment. After a second he realized what Declan had said and he remembered his own men. “Sergeant Lemaire. Corporal Rogg. Private Whittaker. Private Trammel. Harker, Scully, Runyan, McCord, Franklin, Dexter, Jefferson, and Pope. Those were the men in my unit that those things killed. I can’t get them out of my mind.”

His words had no effect on the young man, who rolled back into the bed and buried himself in the bedclothes. “Mine,” he said quietly. “Mine.”

“What’s that?” Chee asked.

“Nothing, I don’t think. He’s just lost. He lost his men. He was in charge. He lost what was his. I know the feeling,” Hollister answered.

Young Declan was quiet again. Knowing there was nothing more for them there, Chee and Hollister left.

Chapter Twenty-two

Chee lay on his bunk, his eyes closed but not sleeping. He stood again on the street in front of the hotel as he had that morning. The hooded figure was reflected in the dining-room window. With his breathing slow and deep, he closed out further distractions from his memory, focusing until all else had dropped away and nothing but the mysterious stranger remained.

Slowly he studied the person who had tried and nearly succeeded in staying hidden. His grandfather’s stern but melodious voice spoke to him from the mists of his memory. “Concentrate, sun jai,” he said. “There is only you and the other.”

Chee circled the figure in his mind, searching for anything to identify who might have followed them.

There was little to see, as if this person wished to travel as anonymously as possible. The duster was long, below the knees, hooded, and covered in a fine layer of dirt. It had no identifying markings that Chee could see.

“Invisibility is not possible, sun jai,” he heard his grandfather say. “We cannot see the wind, but we feel it on our faces. You must look deeper.”

Chee felt the image floating away, and forced more air into his lungs. He circled the black-clad figure again, starting at the head with the face covered completely by the cloak. His eyes traveled downward slowly, looking for anything, a small rip or tear in the fabric, a stain. But he saw nothing until he reached the boots.

In and of themselves, the boots were nothing. Black leather riding boots scuffed by the hundreds of times they had been placed into and pulled out of the stirrups. But they were small. Very small.

Chee knew then, it was a woman following them. The black duster could hide the size of the body. The hat and hood even added height. But the boots could not be disguised. In truth, a small man could be hidden behind the black outfit, but instinctively, Chee knew this was not the case. It was a woman, he was sure of it.

Dog was on the floor next to the bunk when he sat up and alerted, a low growl sounding in his throat. Chee had heard it also. Someone was walking very quietly along the roof of the train.

His holster hung on a peg next to the door of his berth. He slipped the double rig around his waist, buckling it quickly. Quiet again, he listened. There was no sound, but Dog pawed at the door, his ears still straight up. There was an intruder. Someone had gotten past Pinkerton’s guards and into the warehouse where the train was waiting. He opened the door, and Dog charged silently down the hallway, past Hollister’s berth and the galley, to the rear door of the car. He waited, body coiled, until Chee reached the door. Drawing his pistol, he lifted the latch, hoping the door opened with little noise.

“Dog . . . hunt,” he said.

Dog slipped out the door into the darkness.

Chapter Twenty-three

The man-witch knew she was here. He was awake and moving in the car below. Shaniah stood on the roof of the train and heard the door open and the sound of something moving in the night. She smelled a dog immediately and silently cursed. This man who watched over Hollister had a beast at his disposal. With its superior sense of hearing and smell, it would make her task of killing the man-witch much more difficult.

She stepped over to the very edge of the car, looking down. It was nearly pitch-black inside the warehouse, but Archaics see well in the night.

The dog came around the side of the car, its nose to the ground, body tense and rigid. It paused directly below her and stood on its hind legs, front paws against the side of the train, locking eyes with her. But the great animal did not bark and Shaniah wondered why. It was huge: sta

nding as it did, she guessed it was at least six feet tall.

The door opened wider and the man-witch stepped out onto the small metal porch at the back of the train. Time to leave. With the dog watching, Shaniah bent at the knees and leapt high into the air, grabbing a beam in the roof above and climbing up and out of sight. She had come in through a loose soffit vent in the side of the building, but now she waited high above the train, wondering what the man-witch would do. The dog dropped to all fours and sat on its haunches. She watched Chee come forward, his gun in his hand extended but pointing up, not wanting to shoot someone by accident.

“What is it, boy?” he asked, reaching the animal’s side.

The dog whined and barked low in its throat, circling and pawing at the dirt, climbing onto its hind legs again. It looked up into the darkness and though she knew she was invisible to human eyesight in the dark and at this distance, could not help but shrink farther back into the shadows.

The man looked up but could not see beyond a few feet. Shaniah silently cursed the man, for she felt certain he sensed her presence. He had the gift of inhuman stillness. Most humans were impetuous. Not this man. He was careful, thoughtful, and intuitive. But Shaniah had been alive for more than one thousand years and she had learned patience. She would outwait him.

He stood stock-still, as did the dog, which stared up into the darkness like a rattlesnake studying a mouse, waiting for the rodent to twitch so it could strike. Only, in this case, Shaniah was not so certain which of them was the mouse.

More than ten minutes passed, with the man staring silently into the night. Shaniah was about to give up and leave when his voice finally broke the silence.

“I’m watching,” he said quietly to the silence above him. “I’m watching over him. And I know you are there.”

He returned his gun to the holster and turned toward the door. “Come, Dog,” he said. The beast followed dutifully behind its master.

Shaniah waited in amazement until she heard the door click shut, not quite knowing what to think. This man Hollister and his witch Chee were her best chance at finding Malachi, but the man was a problem. If he got in the way . . .

Trail of Fate

Trail of Fate Alcatraz

Alcatraz Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime

Every Zombie Eats Somebody Sometime Keeper of the Grail tyt-1

Keeper of the Grail tyt-1 To Hawaii, with Love

To Hawaii, with Love Out for Blood

Out for Blood The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me The Enemy Above

The Enemy Above Menace From the Deep

Menace From the Deep It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies

It's Beginning to Look a Lot Like Zombies Feeding Frenzy

Feeding Frenzy 3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me

3 The Spy Who Totally Had a Crush on Me Keeper of the Grail

Keeper of the Grail Prisoner of War

Prisoner of War Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill

Jack and Jill Went Up to Kill Live and Let Shop

Live and Let Shop Blood Riders

Blood Riders Ultimate Attack

Ultimate Attack